NEW DEMO

Limits: via Examples (very little algebra)

plus a Calculus example

Limits tend to 'rattle' calculus beginners much like the thumbnail you can click now

![]() .

We hope that a few simple examples calm the beginners because they realty need to get comfortable with limits. We chose examples for verbal content rather than

examples that focus on algebraic functions with graphics. (Our general calculus needs and sources for limits descriptions are numbered. Clicking a number [?] cities the source.)

.

We hope that a few simple examples calm the beginners because they realty need to get comfortable with limits. We chose examples for verbal content rather than

examples that focus on algebraic functions with graphics. (Our general calculus needs and sources for limits descriptions are numbered. Clicking a number [?] cities the source.)

Limits are the foundation of calculus - differential and integral calculus.[1]

This is the first of the three major topics that are covered in a calculus course. Often we use the least amount of time on limits in comparison to the other two topics, differential and integral calculus, but limits are the fundamental foundation in the study of calculus. In particular, limits are part of the formal definition of the other two major topics.[2]

The majority of calculus texts and descriptions of limits start with a variety of short explanations. Here is a short list, some old, others not so old. Choose one you like, find an explanation in your calculus book, or one your instructor likes.

- Limits are a fundamental concept in calculus that helps us understand the behavior of functions as the input values approach a specific point. [3]

- That's the beauty of limits: they don't depend on the actual value of the function at the limit. They describe how the function behaves when it gets close to the limit. [4]

- The most important applications of limits relate to performing a calculation that can not be done at a point of interest, but which can be done at nearby points. A limit corresponds to the estimation of all approximations to a point of interest without testing the actual point of interest. [5]

- In mathematics, a limit is the value that a function (or sequence) approaches as the input (or index) approaches some value. Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis. [6]

- The formal definition of a limit is quite possibly one of the most challenging definitions you will encounter early in your study of calculus; however, it is well worth any effort you make to reconcile it with your intuitive notion of a limit. Understanding this definition is the key that opens the door to a better understanding of calculus. [7]

- In mathematics, a limit is a number that a function approaches as the values of \(x\) plugged into the function approach a fixed number. [8]

- When a Roman approached the limit of his land, he got closer and closer to its boundary. In mathematics a limit is a value that a function gets closer and closer to under certain conditions. [9]

- The limit of a function \(f \) is a tool for investigating the behavior of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) get closer and closer to a particular number \(c\). [10]

- NOTE: In recent calculus texts a 'soft' explanation provides a student with the limit idea, while in calculus texts from a significant number of decades ago provides a more rigorous algebraic explanation of the limit to start with.

- (Circa 1937) "If a variable changes by an unlimited number of steps in such a way that, after a sufficiently large number of steps, the numerical value of the difference between the variable and a constant becomes and remains, for all subsequent steps, less than any pre assigned positive constant, however small, the constant is called the limit of the variable." [11]

- (Circa 1960) "The variable \(\mathbf{v}\) is said to have the constant \(\mathbf{L}\) as a limit when the successive values of \(\mathbf{v}\) are such that \(\mathbf{|L - v|}\) ultimately becomes and remains less than any pre assigned positive number, however small." [12]

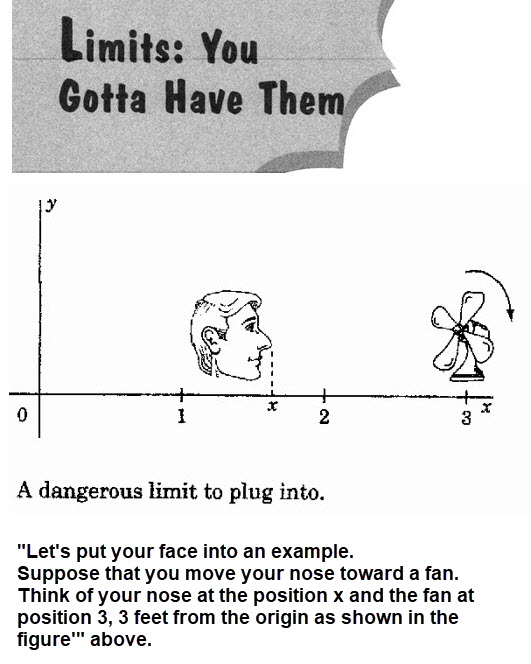

Example 1. Click this thumbnail

![]() to see the text that contains (one of my favorite) examples.

to see the text that contains (one of my favorite) examples.

|

Assignment:Carefully read the face-fan situation. Discuss orally or write a short description of the "limit" as you move your face toward the spinning fan. This is a good place to have a small group merge ideas for this "limit" situation. This is a MATH problem so don't think it is HARD, just imagine how to describe things with out lots of algebra.

The book which contained this example has to have an 'explanation' of the face-fan limit, but don't CHEAT by clicking the thumbnail image below. Wait to Compare your opinion to that of the text.

Example 2, from the Real World:

When it comes to the real world, we find that limits inform us that we need to adjust our "rise" and "run"(slope) to stay within a boundary as we approach it.

And for further practical purposes, limits help us put a finite value on a seemingly infinite journey of precision.

Consider this example, as you drive your car up to a stop sign.

|

You begin to press the brake and your acceleration decreases over time,

and you notice this happening because you can see your speedometer going down. As you get closer to the stop sign,

you work to adjust the rate at which your speed is falling to ensure you will stop at the right spot. You begin to notice that the changes in speed

become a lot less dramatic (but the length of time it takes you to advance your position starts getting a lot longer).

You are slowing down to a point where it is becoming very difficult to see if your speed is still going down.

In theory, you could keep approaching the stop sign infinitely. For each unit of time, you could be half the distance closer then you were before.

However, at some point you say to yourself "this is good enough, I consider myself to have arrived at the stop sign".

You don't want to get a ticket for running through a stop sign, because blaming it on an experiment in Calculus probably won't help you.

You press the brake to the floor for a full stop. The limit zero, pragmatically speaking, is zero for you. You have made your stop.

Example 3, Free Fall:

Free fall is a fundamental concept in physics that refers to the motion of an object where gravity is the only force acting upon it.

In other words, an object in free fall is under the sole influence of gravity, with no other external forces affecting its motion.

An object that falls through a vacuum is subjected to only one external force, the gravitational force, expressed as the weight of the object.

An object that is moving only because of the action of gravity is said to be free falling and its motion is described by Newton’s second law of motion.

In a vacuum the gravitational acceleration is constant and is 9.8 meters per square second at sea level on the Earth.

The weight, size, and shape of the object are not a factor in describing a free fall. In a vacuum, a beach ball falls with the same acceleration as an airliner.

Galileo’s Theory of Motion

The remarkable observation that all free falling objects fall at the same rate was first proposed by Galileo, nearly 400 years ago.

Galileo conducted experiments using a ball on an inclined plane to determine the relationship between the time and distance traveled.

(For details regarding the experiment click here

The incline plane and more..)

He found that the distance depended on the square of the time and that the velocity increased as the ball moved down the incline.

The relationship was the same regardless of the mass of the ball used in the experiment.

The story that Galileo demonstrated his findings by dropping two cannon balls off the Leaning Tower of Pisa is just a legend.

However, if the experiment had been attempted, he would have observed that one ball hit before the other!

Falling cannon balls are not actually free falling – they are subject to air resistance and would fall at different terminal velocities.

In this example we will use a function that provides the distance falling in a vacuum as the time \(\mathbf{t}\) in seconds progresses. From Galileo's work we have that the distance fallen is computed in meters using \[\mathbf{f(t) = \frac{9.8}{2} * t^{2}}\].

It is easy to determine the distance falling for say t = 0, 1, 2, .. and so on. However, when we want the velocity of the falling object at various

a particular time we need to work with some steps similar to the movement of the objects in Examples 1 and 2. For this case we will compute the

\[\text{ average velocity = }\frac{\text{change in position} }{\text{change in time}}\]

Note that we need two changes in data. To emphasize this suppose we want to estimate the velocity at \(\mathbf{t = 3}\) seconds. So we compute

\(\mathbf{f(3) = \frac{9.8}{2} *3^{2} = 44.1} \) meters. We need another time change and another distance change. A reasonable choice is

\(\mathbf{t = 3 + 1}\) with \(\mathbf{f(4)}\). We get that \(\mathbf{f(4) = \frac{9.8}{2} *4^{2} = 78.4} \). It follows that an estimate of the velocity of the falling body

at \(\mathbf{t = 3}\) seconds is about

\[\text{ average velocity = }\frac{\text{change in position} }{\text{change in time}} = \frac{f(4) - f(3)}{4 - 3} = \frac{78.4 - 44.1}{4 -3} = 34.3 \]

This is where a limit idea comes into play. To get a better estimate we repeat the process by shrinking the time change so it gets closer to \(\mathbf{t = 3}\) seconds.

Note that the change in position will also change.

This idea is well represented by a table of time intervals and average velocity shown below.

| Interval | Average Velocity |

|---|---|

| \(3 \le t \le 4\) | 34.30 |

| \(3 \le t \le 3.5\) | 31.85 |

| \(3 \le t \le 3.3\) | 30.87 |

| \(3 \le t \le 3.1\) | 29.89 |

| \(3 \le t \le 3.01\) | 29.45 |

| \(3 \le t \le 3.0001\) | 29.40 |

Now notice that if you look down the interval column and down the average velocity column it appears that time is getting closer to \(\mathbf{t = 3}\) and the "velocity estimates" are approaching \(\mathbf{29.4}\). So the velocity of the falling object at the time \(\mathbf{t = 3}\) plays the role of a "limit". In the language of MATH the limiting value is called the instantaneous velocity which in this little demo is \(29.4 \text{m/s}\).

The preceding computations used some algebra, since we have nice tools we want to use them a bit more in 2 problems.

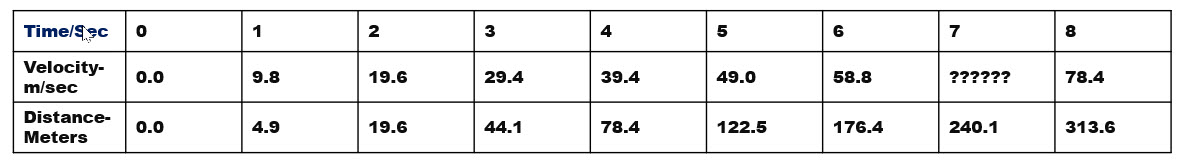

PROBLEM 1. We have a table of data on free fall below.

Estimate the instantaneous velocity at t = 7 using the steps we showed above for t = 3. Note that you can use time intervals to start like

\(7 \le t \le 8\) or \(6 \le t \le 7\) and include others as the times get closer to 7 similar to the work shown above.

Problem 2. Let's use a very tall building that is 541 meters high. Click here

![]() to see the building.

to see the building.

(a) Determine the time in seconds that a free fall object to reaches the middle of the building.

(b )Explain how to estimate the instantaneous velocity of the object when it reaches the midpoint of the height.

Example 3.The idea of approaching a limit occurs in elementary geometry. We will show how to fill a circle using regular polygons.

Regular polygons have that all sides are equal, all its interior angles are equal, and the sum of its exterior angles is 360°.

To see regular polygons with sides 3 through 10 click this thumbnail

![]() .

.

The area of a regular polygon is the area that is enclosed by it. It is generally measured in square units.

The area of a regular polygon depends on \(\mathbf{n}\) the number of sides. Click the following MP4 file to see

regular polygons with sides 3 through 8 start filling a circle. Note that the areas increase as the number of sides increase.

Show regular polygons in a circle.

Next we fill the area of each of the regular polygons as they are shown in the circle. Note that the filling overlaps but you should get a feel

for the area increasing within the circle for each regular polygon which is displayed. Click this MP4 file.

Show regular polygons filled.

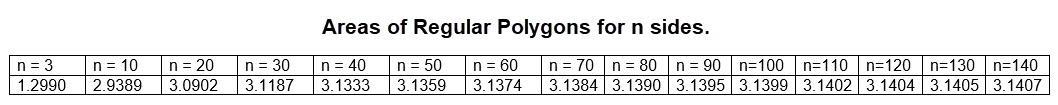

Problem 1. Let's determine areas of regular polygons as the number of sides, \(\mathbf{n}\), increases. Based on the data shown in the figure below estimate the 'geometric limit' for the area of regular polygons that are within the circle shown in the MP4 files which can be viewed above.

|

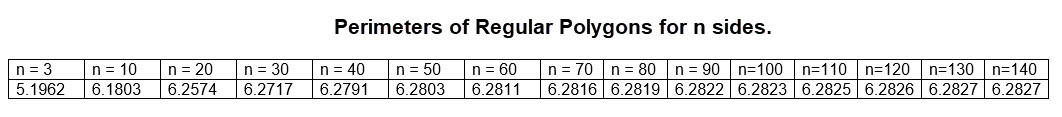

Problem 2. We are dealing with geometry in this example. In geometry where there areas are involved you often deal with perimeters, which is the case here. Let's determine perimeters of regular polygons as the number of sides, \(\mathbf{n}\), increases. Based on the data shown in the figure below estimate the 'geometric limit' for the perimeters of regular polygons that are within the circle shown in the MP4 files which can be viewed above.

|

Example 4, Calculus Based.

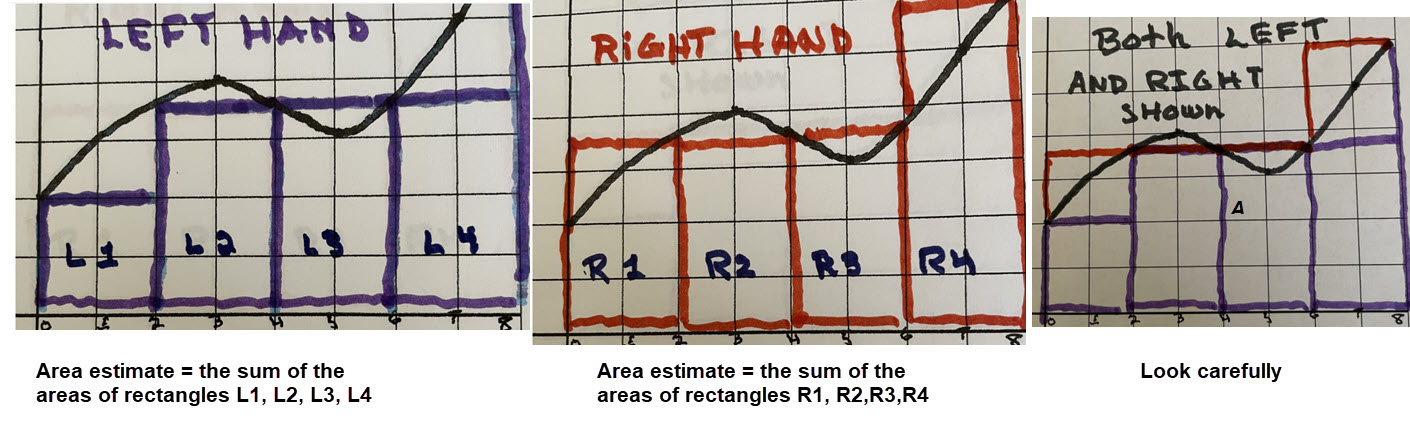

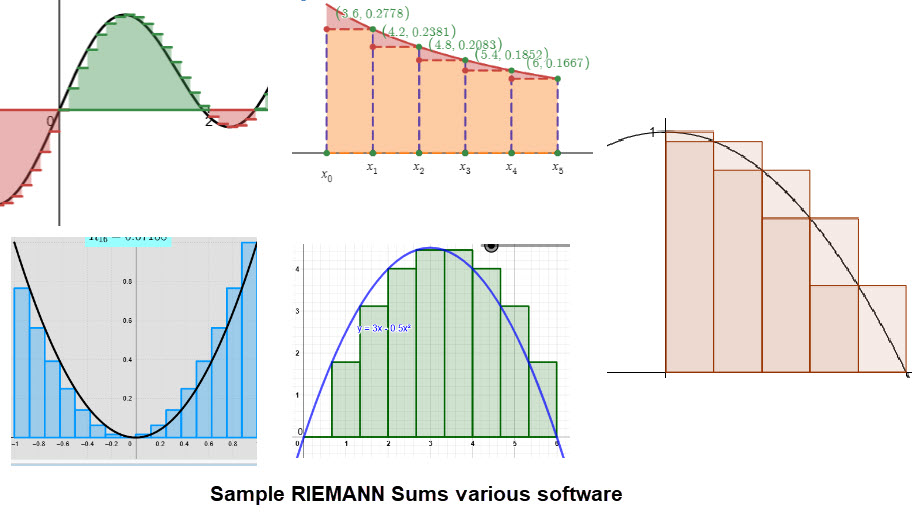

The area under a curve can be estimated using various methods, one method is called Riemann Sums.

Riemann sums are a way to approximate the area under a curve by dividing the area into small rectangles and summing their areas.

Here we will construct the rectangles using the left-endpoint and right-endpoint for each subinterval that holds the rectangle.

We chose a simple curve where we used the base of rectangles to be 2 units.

When we use Left Hand Rule we make a rectangle of height \(\mathbf{f(left\; end)}\) based on the left coordinate of a subinterval.

Similarly, when we use the Right Hand Rule we make a rectangle of height \(\mathbf{f(right\; end)}\) based on the right coordinate of a subinterval.

A "crude" example is shown next.

|

|

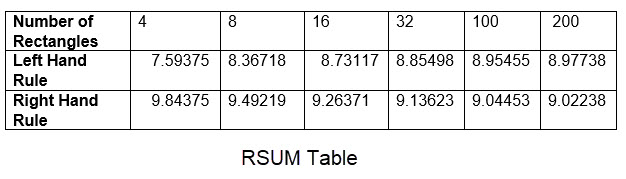

When we use both left and right hand rules this provides two estimates of the area under the curve with the possibility of getting a limit estimate situation that can "squeeze" the value of the limit of the true area. As an example of "squeezing" the limit using Riemann sums look at the following table.

|

Using the RSUM table what is your guess for the limit of the area under the curve \(\mathbf{f(x)}\) used to generate the data? (Keep it simple.)

==================================================================

SOURCES:

[1] What are limits in calculus?

[3] AI Brave Search

Consider the task of finding the area of region on a grid where the shape is curved and there is no simple geometric rules to find the answer. A very nice situation in which you can change the grid to count squares within the region as an estimate. There are two hands-on examples very worth reading.[7] 7. Why you need a formal definition of a limit

[8] This was taken from Page 46 in the book How to Ace Calculus: The Streetwise Guide, by C. Adams, J. Hass, and A. Thompson, W, H. Freeman and company, New York, 1998 for a quick description of a function with a limit involved.

[9] This was taken from Page 127 in the Words of Mathematics, An Etymological Dictionary of Mathematical Terms Used in English, by Steven Schartzman, The Mathemaical Association of America, 1994

[10] This was taken from Page 85 in Single Variable Calculus , Second Edition, by G. Bradley and K. Smith, Prentice Hall, 1999

[11] This was taken from Calculus, Herman W. March and Henry C Wolff , McGraw-Hill, Book Company, Inc., New York and London, 1937

[12] This was taken from Analytic Geometry and Calculus, William R. Longley, Percy F Smith, and Wallace A Wilson, Ginn and Company, 1960

Other Interesting ITEMS:

- What is a Regular Polygon.

- Area of regular polygons.

- Good definitions.

- Length of the side of a regular polygon.

- List of names of regular polygons.

- Interesting discussion of geometric limits.

- The most important applications of limits relate to performing a calculation that can not be done at a point of interest, but which can be done at nearby points. A limit corresponds to the extrapolation of all approximations to a point of interest without testing the actual point of interest.

- Limit example in GeoGerbra.

- Another example in GeoGerbra.

Riemann Sums Software:

- Desmos R Sums.

- Another Desmos R Sums.

- GeoGerbra R Sums.

- Another GeoGerbra R Sums.

- More GeoGerbra R Sums.

- There are lots of other RSUMS code; use your browser.

==============================

NOTES:

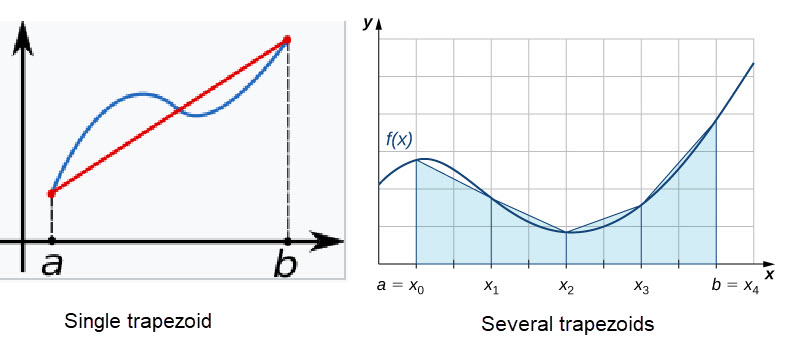

Area under a curve can be estimated in a variety of ways.

Trapezoidal Rule

The Trapezoidal Rule is a simple and effective method for approximating the area under a curve. It works by dividing the area into smaller trapezoids and summing their areas.

Formula: \[\mathbf{Area ≈ \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}\frac{(x_{i+1}-x_i)(y_{i+1}+y_i)}{2}} \]

where \(x_i\) and \(y_i\) are the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates of the \(i^{ th}\) point, respectively, and \(n\) is the number of points.

|

Other methods for estimating the area under a curve include:

Simpson’s Rule: A more accurate method than the Trapezoidal Rule, which uses parabolic segments instead of trapezoids.

Monte Carlo Integration: A method that uses random sampling to estimate the area under a curve.

For information on this method go to

Monte Carlo Area Simulations. Then click on the title Monte Carlo Area Simulations.

There are activities to use to get a feel for the method.

Numerical Integration: A method that uses numerical methods to approximate the area under a curve.

Choose the method that best suits your needs and the complexity of the curve.

- Trap Rule in Wikipedia.

- Several techniques.

- A portion of the descriptions above are from an AI search using browser Brave.

==================================================================

David R Hill 7/6/2024

LIMITS

https://mathdemos.org/